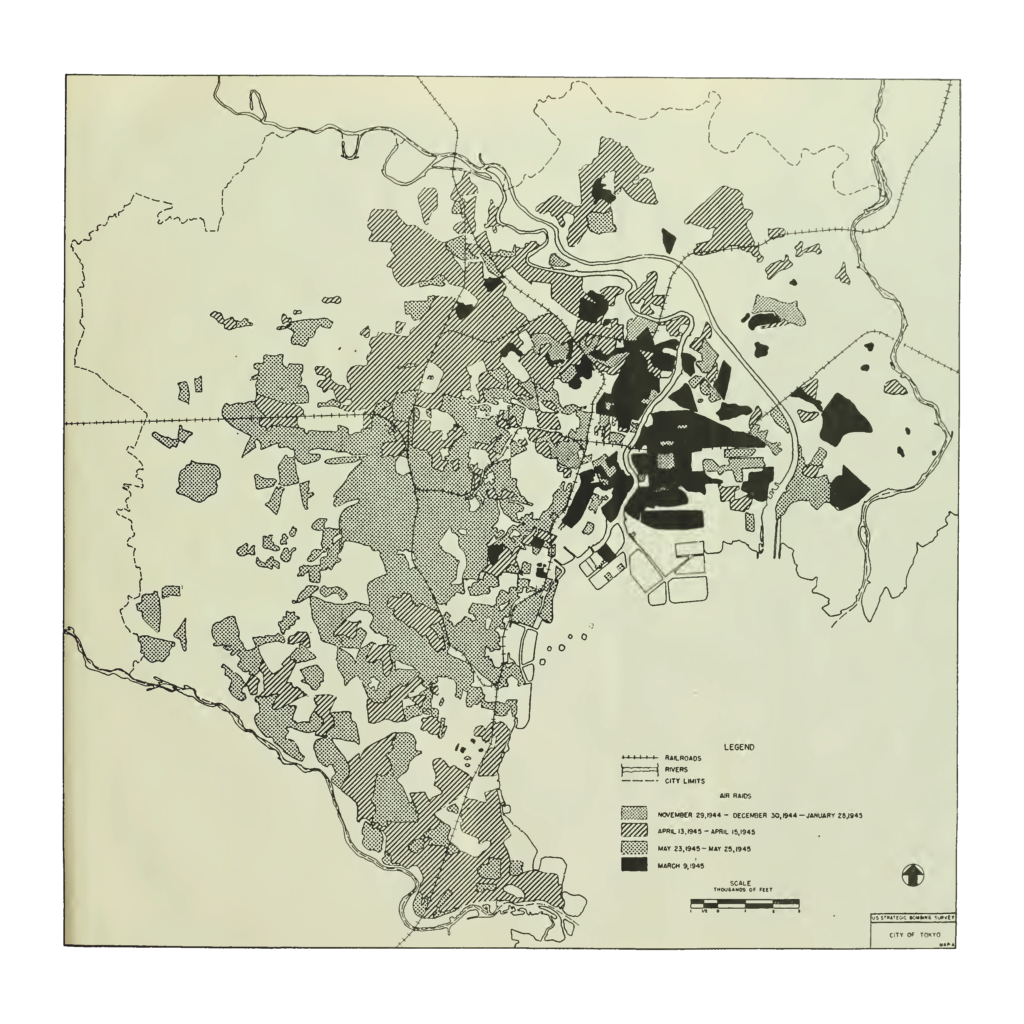

The fundamental mission of the 330th ASG was to keep the B-29s at Isely Field flying missions against Japan. This they did. Supported by the the 330th and the other three ASGs at Isely Field, the 73rd Bomb Wing dropped 48,532 tons of bombs on Japanese targets in the course of 9894 combat sorties.

The first B-29 to arrive at Isely Field was T Square 5 on 12 October 1944. She was Brigadier General Haywood “Possum” Hansell’s plane. General Hansell was the commander of the XXI Bomber Command (all the B-29s outside of India and China). The crew wanted to name the plane “Joltin Josie.” General Hansel preferred “The Pacific Pioneer.” In a wonderfully un-military compromise, the plane would be named “Joltin Josie, The Pacific Pioneer.” Her arrival on Saipan caused quite a stir – finally, four months after invading the island, the B-29s were arriving and the mission to strike at Japan was almost at hand.

Starting in November, General Hansell would try to strike at Japan by applying Army Air Forces doctrine – high altitude precision strikes against strategic targets. The limitations of bombing technology, teething problems with the new B-29s, and the weather over the Japanese home islands would frustrate his attempts more often than not. Before he could “work out the kinks” and begin producing the results expected in Washington, he was relieved in January 1945. General Curtis LeMay would assume command – and two months later the low-level incendiary attacks would begin.

Joltin Josie lasted only a few months longer than General Hansell. She successfully flew 24 missions without an abort. But, on 1 April 1945 she crashed on takeoff (see discussion below) just off the end of the Isley Field runways, exploding on impact with the waters of Magicienne Bay. There were no survivors.

The photo above was used in hundreds of thousands of propaganda leaflets dropped over Japan in the last weeks of the war. By that time the threats to the B-29s had diminished enough that the US was “calling its shots” as a show of strength. The text of the leaflet that accompanied the photo said:

ATTENTION

JAPANESE PEOPLE

In the next few days the military installations in SOME OR ALL of the cities named on the photograph will be destroyed by American bombs. These cities contain military installations and workshops or factories which produce military goods. The American Air Force, which does not wish to injure innocent people, now gives a warning to evacuate the cities named and save your lives. America is not fighting the Japanese people. The peace which America will bring will free the people from the oppression of the military clique and mean the emergence of a new and better Japan. You can restore peace by demanding new and good leaders who will end the war. We cannot promise that only these cities will be among those attacked, but SOME OR ALL will be, so heed this warning and evacuate these cities immediately.

Of course, not every mission was without losses and the earlier B-29 attacks against Japan were progressively more perilous. Over the course of the war, the 73rd Bomb Wing (one of five B-29 Bomb Wings operating out of bases in the Mariana Islands) lost 182 aircraft and had another 1044 cases of battle damage. 1033 men were killed or missing, and another 138 men were wounded.

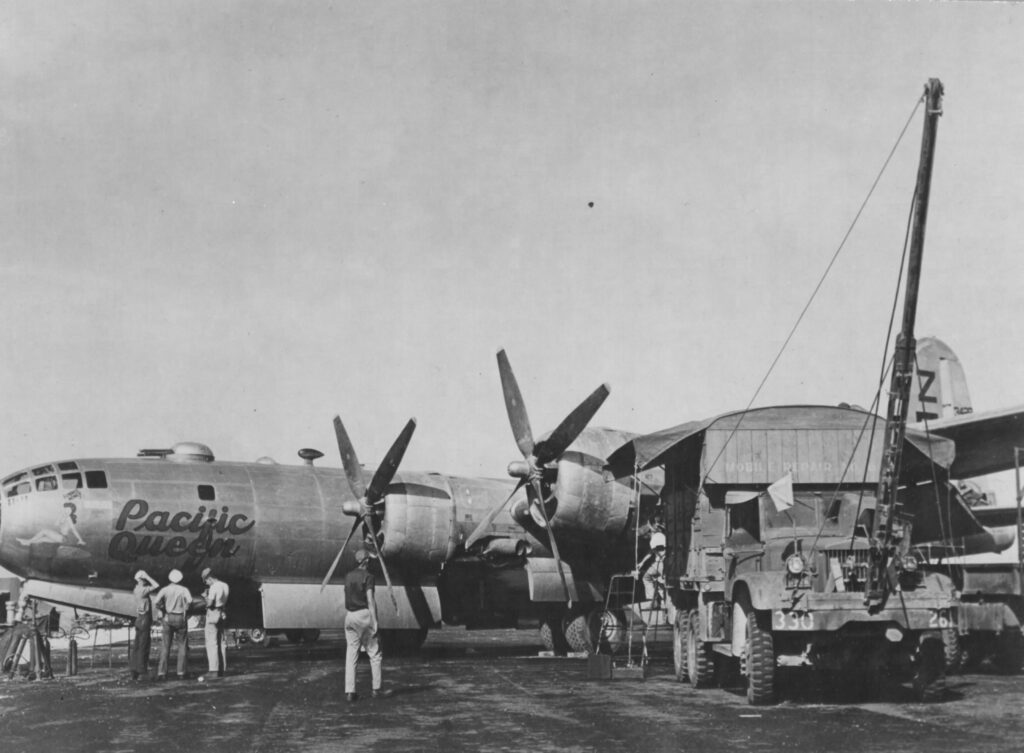

In addition to battle damage, running out of fuel, and possible errors navigating over vast stretches of open ocean, the B-29 itself could cause a crew to be lost. The B-29 had been rushed into service on a highly accelerated delivery schedule which limited flight testing. Consequently, the plane began service with some significant engineering weaknesses, including engines that were susceptible to overheating and fire. These engines were considered “still not ready for combat” even as the first B-29s were being sent overseas for combat.

Design modifications to address these weaknesses were made after the aircraft were delivered. Through time these many of these weaknesses would be addressed and the dependability of the B-29 would progressively improve. But the dependability of the B-29s powerful R-3350 engines would always remain something of a concern.

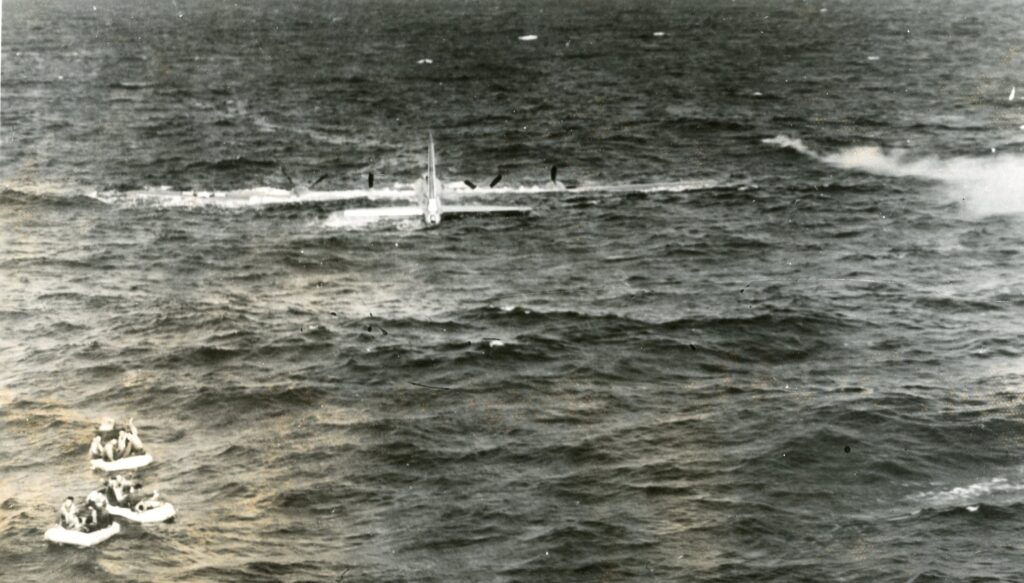

As the photo above shows, ditching at sea – even near land – was extremely dangerous. During the period of the B‑29 attacks on Japan (November 1944 – August 1945), search and rescue activities for downed flight crews continuously improved and the chances of being rescued if you had to ditch or bail out got progressively better. However, it was still not unheard at any time for a B-29 to take off from Saipan, Tinian, or Guam (the three Mariana Islands that ultimately had B-29 bases) and never be heard from again. Overall, 709 B-29 crewmen from the 73rd Bomb Wing were known to have ditched at sea. Only 285 of them (40%) were recovered.