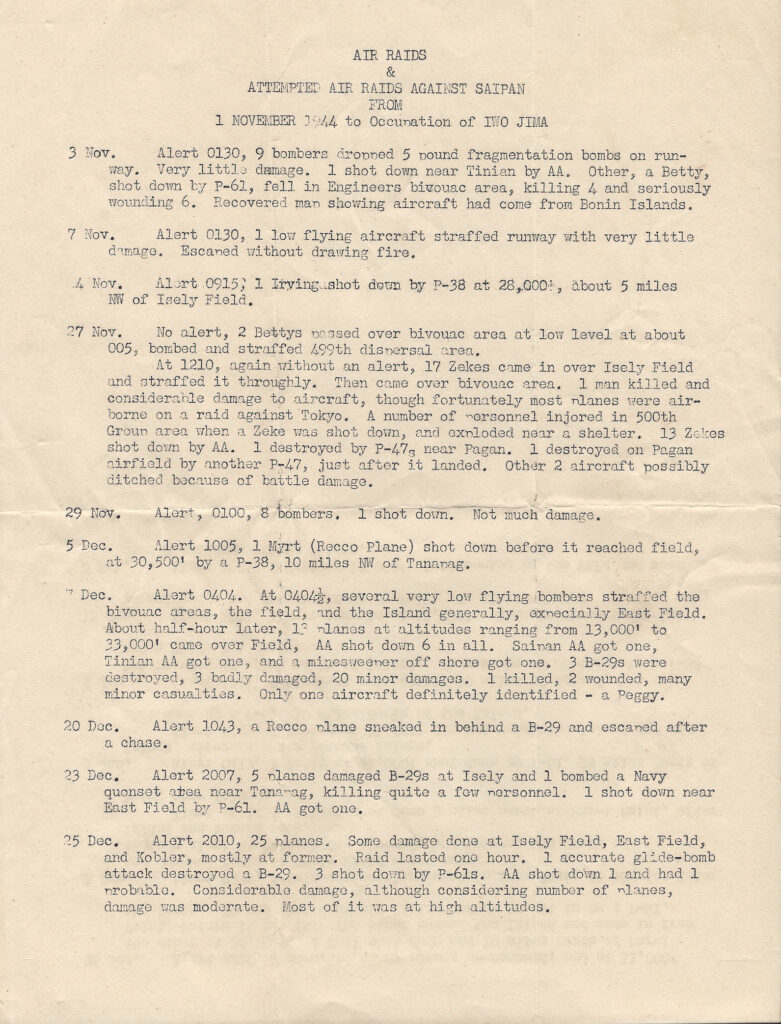

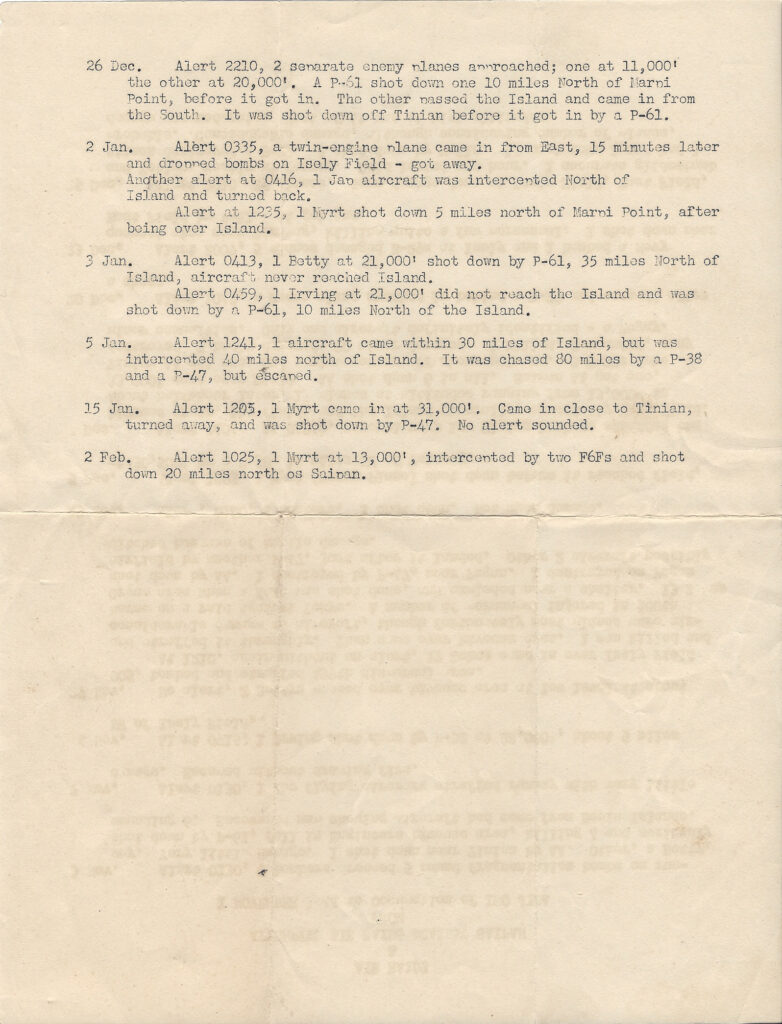

Isely Field was subjected to several successful Japanese air raids between November 1944 and January 1945. Some of these raids damaged or destroyed several B‑29s, killed and injured men on the ground, and damaged facilities across the island. The next two images summarize these raids.

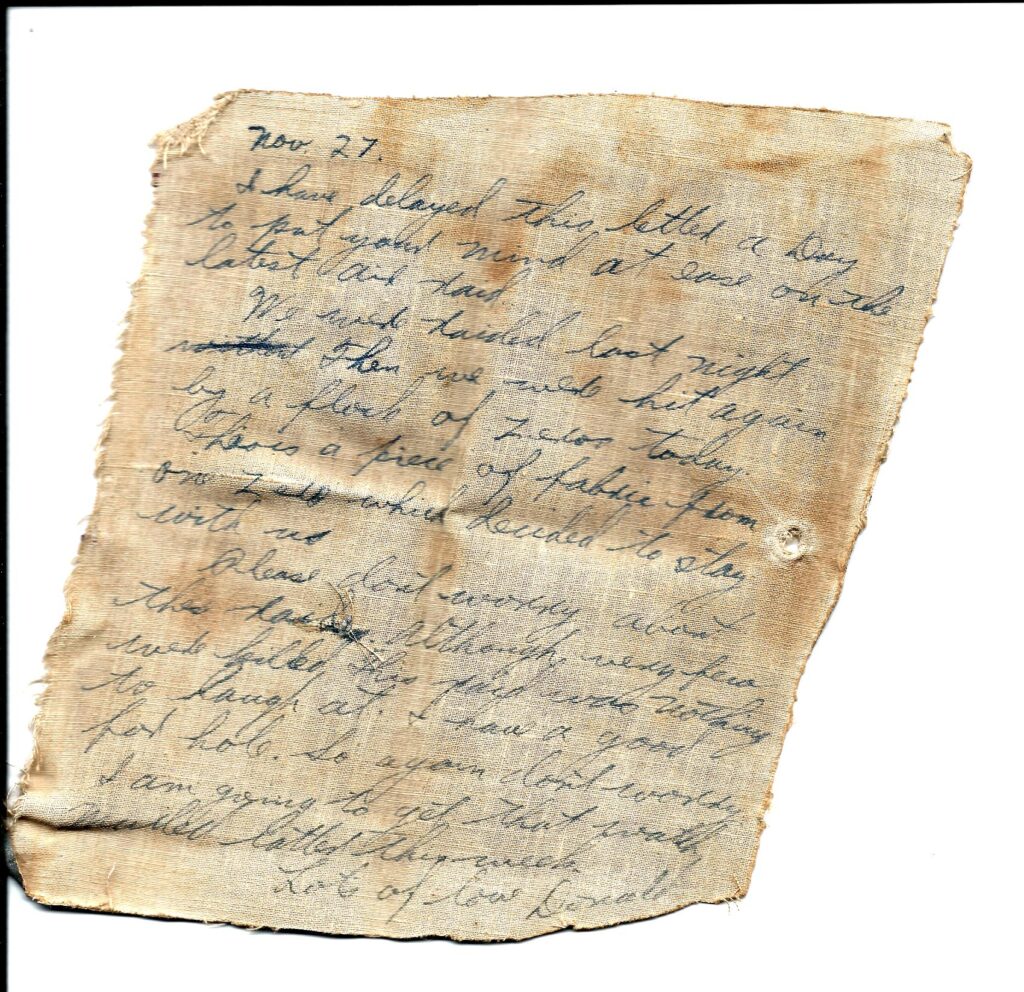

Many years after the war, Corporal Donald Dundon wrote about his experience during the 27 November 1944 Japanese air raid on Isely Field, Saipan. This is an excerpt from his notes.

“It was our custom during the noon hour to hurry though our meal in the mess hall and then grab a few minutes of sack time in our tents. At about five minutes before 1 p.m., we would all walk up to the flight line to our repair shops. And we were on double daylight-saving time. On this day, double daylight-saving time would mean a lot.

Our quick nap was interrupted by Japanese machine guns and the roar of a squadron of fighters. 17 Zekes had come in at sea level, under our radar and the first anyone knew about them was when they opened up on our B-29s. Fortunately, most of our airfield’s 180 bombers were in the air, on their way to bomb Japan.

Amidst the roar of airplanes and antiaircraft guns, I made my way to a foxhole I had prepared some weeks earlier. Thoroughly scared, I hunkered down in the hole and missed as lot of the action. When I did renew my courage and look out, I saw one Zeke taking evasive action over the sea as the antiaircraft guns tried to splash him down with hits below him.

I am not certain, but I think this was the plane that a few second later crash-landed on the ball field in the bomber squadron living area down the hill from us. The story goes that this pilot survived the crash, but as he tried to climb out of his burning cockpit, dozens of 30-cal. carbines fired in unison and the pilot fell back into the flames.

I never saw the Zeke fall that crashed on an empty hard stand, just across the taxiway from our sheet metal shop. The B-29 that was usually parked there was in the air near Japan.

After the all-clear was sounded, we headed for the flight line to see the damage. There were a number of cannon and machine gun bullet holes in our shop building to remind us of the benefits of double daylight-saving time. From the shop, we walked over to see the remains of the Zeke. I remember that the plane had come in pretty hard and there had been some fire. The pilot’s body was gruesome. He lay on the ground, a headless torso minus arms from the elbows down and legs that ended at the knees.

Today, I am surprised at how callous a 20-year-old I could be. Then, I was more bent on a souvenir. Looking back to the rear of the wreckage, I saw that the tailplane had not burned. Whipping out my pocketknife, I cut out a rough square of fabric and stuffed it in my pocket. When the day was over, I had determined to write a letter home on the back side of that fabric. I did so the next day, and to my surprise the military censors let it go through.”

Editor’s note: Minor grammatical edits were made to the preceding text.

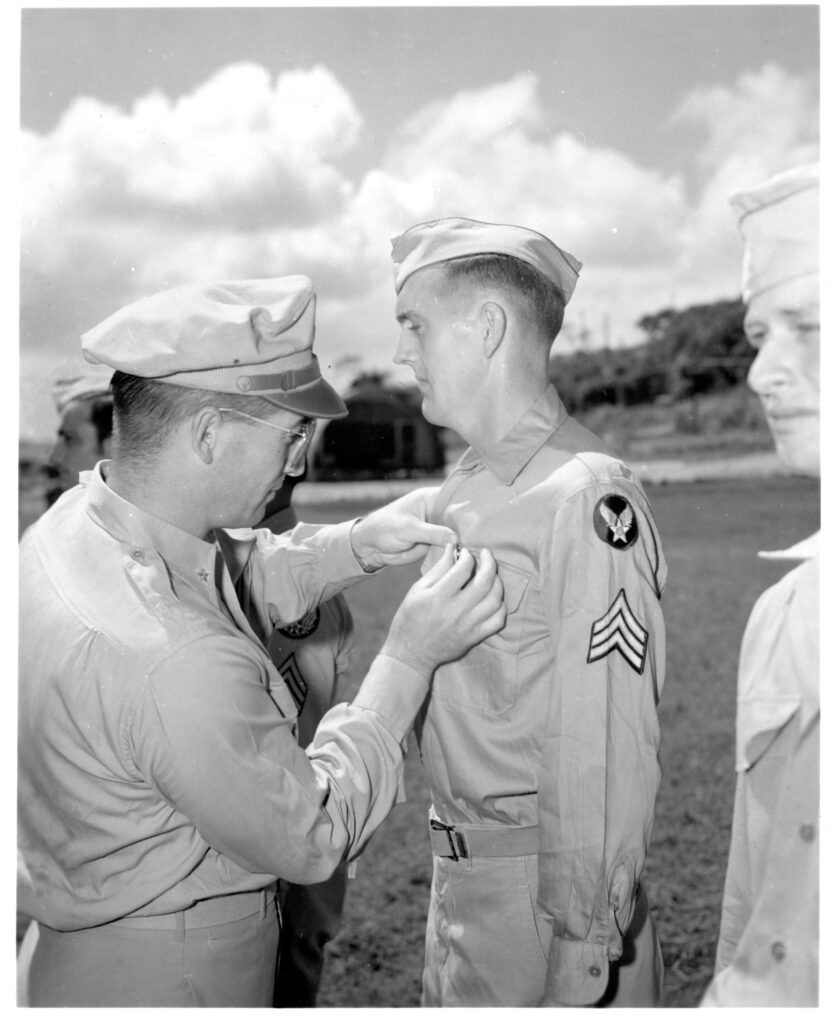

After the raid on 7 December 1944 “not a tent was without holes” in the 330th ASG’s area. For his actions during this raid, Sergeant Charles Nash won the Bronze Star for “heroic achievement in connection with military operations against the enemy.” Although he was a photographer, he volunteered to help the Fire Fighting Section after the Japanese attack set a number of B‑29s on fire. His citation states:

“At great personal risk Sergeant Nash operated a water carrier and by doing so kept two fire crash trucks in operation. Much of the action occurred during continued enemy strafing. By his volunteer action, Sergeant Nash saved much valuable property and equipment for the government and probably prevented the loss of life that would have resulted from explosion of the gas-loaded planes.”